Everyone knows that Harriet Tubman has many ties to Beaufort, SC and had done lots of work to help enslaved people find their freedom, but the Combahee Ferry Raid on June 2, 1863 in what is today known as Green Pond, SC, has cemented her place in history.

They called her “Moses” for leading enslaved people in the South to freedom up North. But Harriet Tubman fought the institution of slavery well beyond her role as a conductor for the Underground Railroad. As a soldier and spy for the Union Army during the Civil War, Tubman became the first woman to lead an armed military operation in the United States.

Tubman had been in South Carolina as a volunteer for the Union Army. With her family behind in New York, and having established herself as a prominent abolitionist in Boston circles, Tubman, at the request of Massachusetts Governor John Andrew, had gone to Hilton Head, SC, which had fallen to the Union Army early in the war.

For months, Tubman worked as a laundress, opening a wash house, and serving as a nurse, until she was given orders to form a spy ring.

Tubman had proven herself invaluable at gathering clandestine information, forming allies and avoiding capture, as she led the Underground Railroad.

In her new role, Tubman assumed leadership of a secret military mission in the SC Lowcountry.

Partnered with Colonel James Montgomery, an abolitionist who commanded the Second South Carolina Volunteers, a Black regiment, together the two planned a raid along the Combahee River, to rescue enslaved people, recruit freed men into the Union Army and obliterate some of the wealthiest rice plantations in the region.

Montgomery had around 300 men, including 50 from a Rhode Island Regiment and Tubman rounded up eight scouts, who helped her map the area and send word to enslaved people when the raid would take place.

The night of June 1, 1863, Tubman and Montgomery, on a federal ship the John Adams, led two other gunboats, the Sentinel and Harriet A. Weed, out of the St. Helena Sound towards the Combahee River. En route, the Sentinel ran aground, causing troops from that ship to transfer to the other two boats.

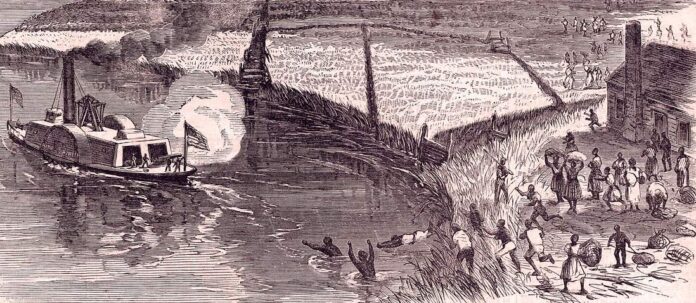

Around 2:30 a.m. on June 2, the John Adams and the Harriet A. Weed split up along the river to conduct different raids. Tubman led 150 men on the John Adams toward the fugitives. Tubman, later commenting on the raid, said once the signal was given, she saw slaves running everywhere, with women carrying babies, crying children, squealing pigs, chickens and pots of rice. Confederate soldiers tried chasing down the slaves, firing their guns on them. One girl was reportedly killed.

As the escapees ran to the shore, Black troops in rowboats transported them to the ships, but chaos ensued in the process. Tubman, who didn’t speak the region’s Gullah dialect, reportedly went on deck and sang a popular song from the abolitionist movement that calmed the group down.

More than 700 escaped slavery and made it onto the gunboats. Troops also disembarked near Field’s Point, torching plantations, fields, mills, warehouses and mansions, causing a humiliating defeat for the Confederacy, including the loss of a pontoon bridge shot to pieces by the gunboats.

The ships docked in Beaufort, where a reporter from heard what had happened on the Combahee River.

He wrote a story without a byline about the “She-Moses” but never mentioned Tubman’s name. He wrote that Montgomery’s “gallant band of 300 soldiers under the guidance of a Black woman, dashed into the enemies’ country, struck a bold and effective blow, destroying millions of dollars worth of commissary store, cotton and lordly dwellings, and striking terror to the heart of the rebeldom brought off bear 800 slaves and thousands of dollars worth of property, without losing a man or receiving a scratch.”

But Tubman’s anonymity came to an end in July 1863 when Franklin Sanborn, the editor of Boston’s Commonwealth newspaper, picked up the story and named Harriet Tubman, a friend of his, as the heroine.

Despite the mission’s success, including the recruitment of at least 100 freedmen into the Union Army, Tubman was not compensated for her efforts on the Combahee Ferry Raid. She had petitioned the government several times to be paid for her duties as a soldier, but she was denied because she was a woman; even though the Harriet Tubman led raid on the Combahee cemented her place in history.

Tubman would eventually get a pension, but only as the widow of a Black Union soldier she married after the war, not for her courageous service as a soldier.

Harriet Tubman died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913 in Auburn, New York. While we don’t know her exact birth date, it’s thought she lived to her early 90s.

The bridge that carries Highway 17 over the Combahee River just up the road from Beaufort in Green Pond, SC, has since been named the Harriet Tubman Bridge, and there is a new Harriet Tubman Monument erected in her honor at the historic Tabernacle Baptist Church on Craven Street in downtown Beaufort SC, where she is said to have stayed and “hid.” The monument was be erected next to the grave site of another Black Civil War hero named Robert Smalls.

Cover photo originally in Harpers Weekly, published July 4, 1863. Reworked and used from “Union troops raid Confederate plantations on the Combahee River, June 1-3, 1863, artist’s impression, detail,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College